What is Dissociation as a Defence?

The Ash Lad and the Golden Bird, Painting by Theodor Kittelsen, 1900

Dissociation is a psychological defence mechanism that allows an individual to separate themselves from thoughts, feelings, emotions, or experiences that feel overwhelming. In psychodynamic psychotherapy, it is understood as a way the mind protects itself from overwhelming anxiety, trauma, distress or internal conflict by creating distance from existing realities. The psyche then temporarily splits off awareness to preserve functioning and reduce psychological suffering, rather than confronting painful experiences directly.

Patients who rely on dissociation may describe feeling detached from their bodies, emotions, conversations, or surroundings. Some experience memory gaps or a sense that events are happening in a dream-like state. This defence can lead to difficulties with emotional regulation, identity, communication, and relationships when it becomes a persistent coping style even though it can be adaptive in the short term, especially in response to trauma. In therapy, these disruptions are gently examined so that patients can reconnect with their internal experiences at a pace that is tolerable.

From a psychodynamic perspective, dissociation demonstrates the mind’s attempt to manage unconscious conflict. It removes awareness altogether and creates a sense of distance between the self and painful content which can delay integration of memory and emotion, but it also offers insight into the individual’s history of coping with overwhelming circumstances. Therapy seeks to understand the developmental roots of dissociation and how it continues to influence the person’s current life.

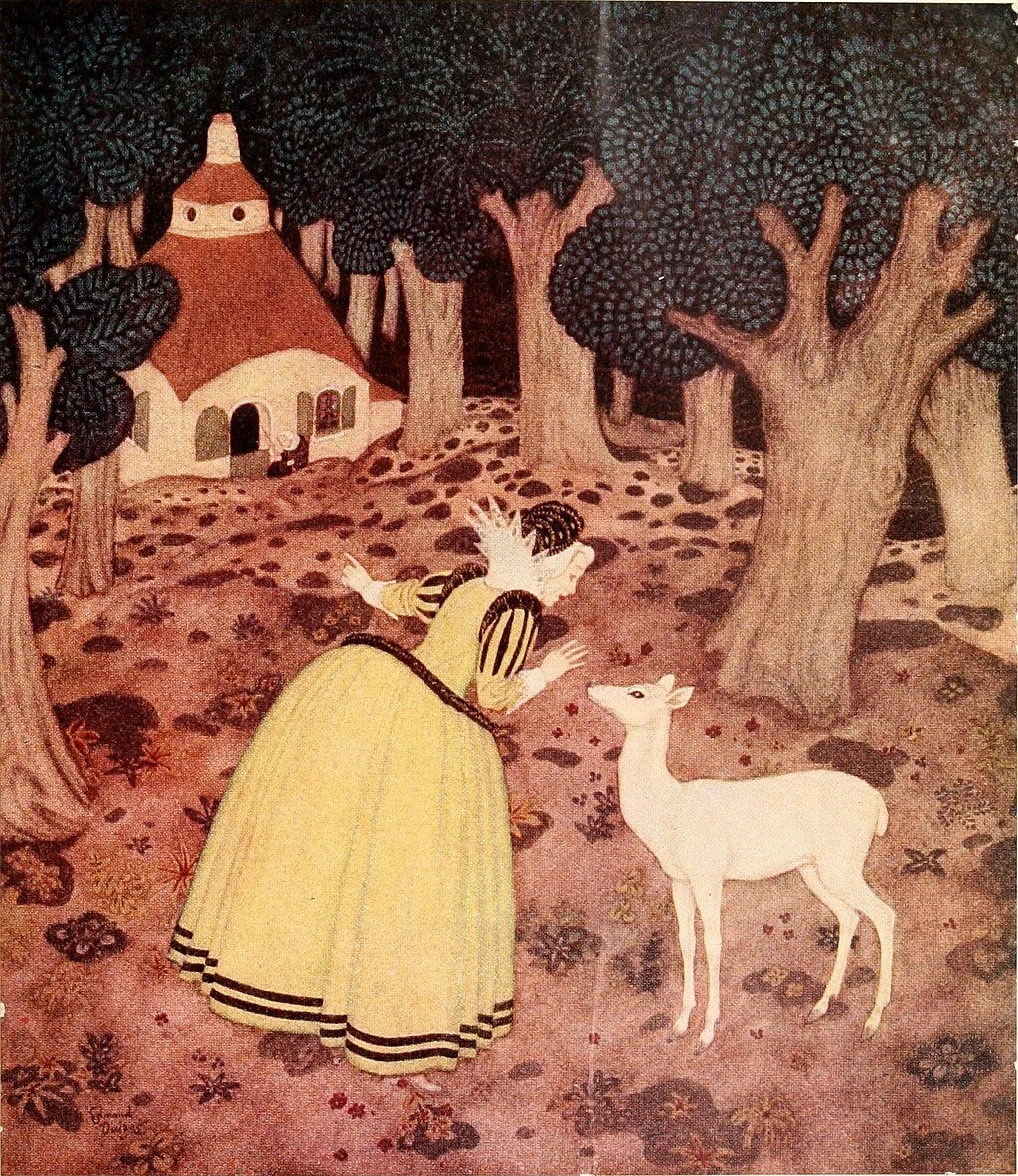

Fairy Book, Color Plate, Illustration by Edmund Dulac, 1917

George Vaillant, in his work on defence mechanisms, placed dissociation within the spectrum of defences that range from immature to mature. He identified dissociation as an intermediate or neurotic defence, which is more adaptive than primitive mechanisms like denial, but less adaptive than mature defences such as humour. His framework helps clinicians understand not only the protective function of dissociation, but also its limitations.

In psychodynamic psychotherapy, the goal is not to eliminate dissociation but to help patients gradually shift it into healthier forms of coping. Patients are then invited to notice and name dissociative experiences and link them to underlying conflicts or trauma, all while maintaining a safe therapeutic relationship. In doing so, dissociation shifts from being an automatic defence to a conscious signal that something important requires attention. With time, patients can develop greater resilience and self-understanding.